Well, knock me down with a feather

Gillian Lord visits the Scottish Parliament Building, and leaves amazed at the architectural and artistic genius of it all

What I knew about the ‘new’ Scottish Parliament building at Holyrood could be reduced to dot points: That the cost blew out by hundreds of millions. That it was years late in construction. That it was roundly criticised, called controversial and even scandalous. And then I saw it for myself.

I was blown away by a building that is at once practical, poetic, and a work of art. It is inspirational, layered with powerfully simple symbolism and meaning, rich in detail, at once quiet and soaring.

I’ve been inside a fair few parliament buildings and this one is striking for the way it feels part of the city and nature around it, for its glorious abundance of natural light, and for its overwhelming sense of inclusivity. Here you are part of the world around you, and it is part of the building.

It is a triumph of design for the Catalan architect Enric Miralles who, along with his second wife and fellow architect Benedetta Tagliabue, founded the firm EMBT Architects, who were awarded the contract to design the building in 1998.

Sadly Miralles died of a brain tumour aged 45 in 2000 before he could see its completion. The Scottish Parliament Building would be his magnum opus.

For the Scottish people

He wanted the building to reflect Scottish identity and the connection between Scottish people and nature. He also wanted it to represent all of Scotland, to be a place for all, and to portray the dialogue between Scottish people and the land. In keeping with this, he wanted the building to be an extension of the land.

“We don't want to forget that the Scottish Parliament will be in Edinburgh, but will belong to Scotland, to the Scottish land. The Parliament should be able to reflect the land it represents. The building should arise from the sloping base of Arthur's Seat and arrive into the city almost surging out of the rock.”

— Enric Miralles, 1999

Renowned American landscape designer and architectural historian Charles Jencks described it as “a tour de force of arts and crafts and quality without parallel in the last 100 years of British architecture". (Jencks, incidentally, is also co-founder of the Maggie’s Cancer Care Centres, but I digress).

The history and the fuss

In 1997 Scots voted for more devolved powers and the then-Secretary of State for Scotland, Donald Dewar, decided a new, purpose-built facility would be constructed in Edinburgh to house the Scottish Parliament.

And so began the journey to the Parliament Building – actually a complex of several buildings - that stands today in Holyrood, within the UNESCO World Heritage area in central Edinburgh and home to 129 MSPs and more than 1,000 staff and civil servants. The complex covers an area of 1.6ha (or four acres).

The choice of Miralles was initially controversial partly because he wasn’t Scottish, and because his design was considered radical and too adventurous for some.

In an ultimate vindication, his post-modernist building went on to win the Royal Institute of British Architects prestigious Stirling Prize in 2005, where it was voted the best new building of the year. You can link to an historic Guardian article on that here.

The cost! Scandal!

Next, the cost. Originally estimated at between £10 million and £40 million, these costs blew out to an eventual £414 million, and much howling of outrage.

A resulting inquiry headed by Lord Fraser of Carmyllie noted that the initial estimate was hopelessly naïve, it was always going to cost more, and that changes to design requirements and a reliance of ‘inaccurate information from civil servants’ were all contributory factors, but ultimately there was no single ‘villain of the piece’.

Even so, £414 million feels like nothing 10 years later, when measured against the likes of an estimated £4 billion wasted in PPE contracts and the like during the Covid pandemic - not to mention the personal wealth of so many today exceeding that by millions.

And yes, it was indeed late in completion. Originally intended to finish in 2001, the new Parliament was finally declared open for business by Queen Elizabeth II on 9 October 2004.

But enough about that – it’s a long story, with many moving parts. The Wikipedia entry is a good place to learn more detail.

Let’s go instead to another glorious autumn day and a journey through Fife countryside, vivid in autumn livery, to the city of Edinburgh and a visit to the Scottish Parliament Building at the bottom of the Royal Mile, with the Palace of Holyroodhouse (where the reigning monarch stays when visiting) nearby.

With the young lad, who is on Parliamentary staff, as our guide, and it being a Saturday in Parliamentary recess, we were able to see so much of this building, including the modest, efficient offices where MSPs and their staff work, committee rooms, relaxation areas, and of course the Debating Chamber itself.

In keeping with Miralles’ vision of culture and harmony with nature, his inspiration for the roof of the Tower Buildings, for example, came from Edwin Lutyens’ sheds, made from upturned herring boats.

Millares’ desire to represent Parliament as a growing thing is also represented by the rooflights in the Garden Lobby, constructed from stainless steel covered by a latticework of oak struts, which resemble leaves.

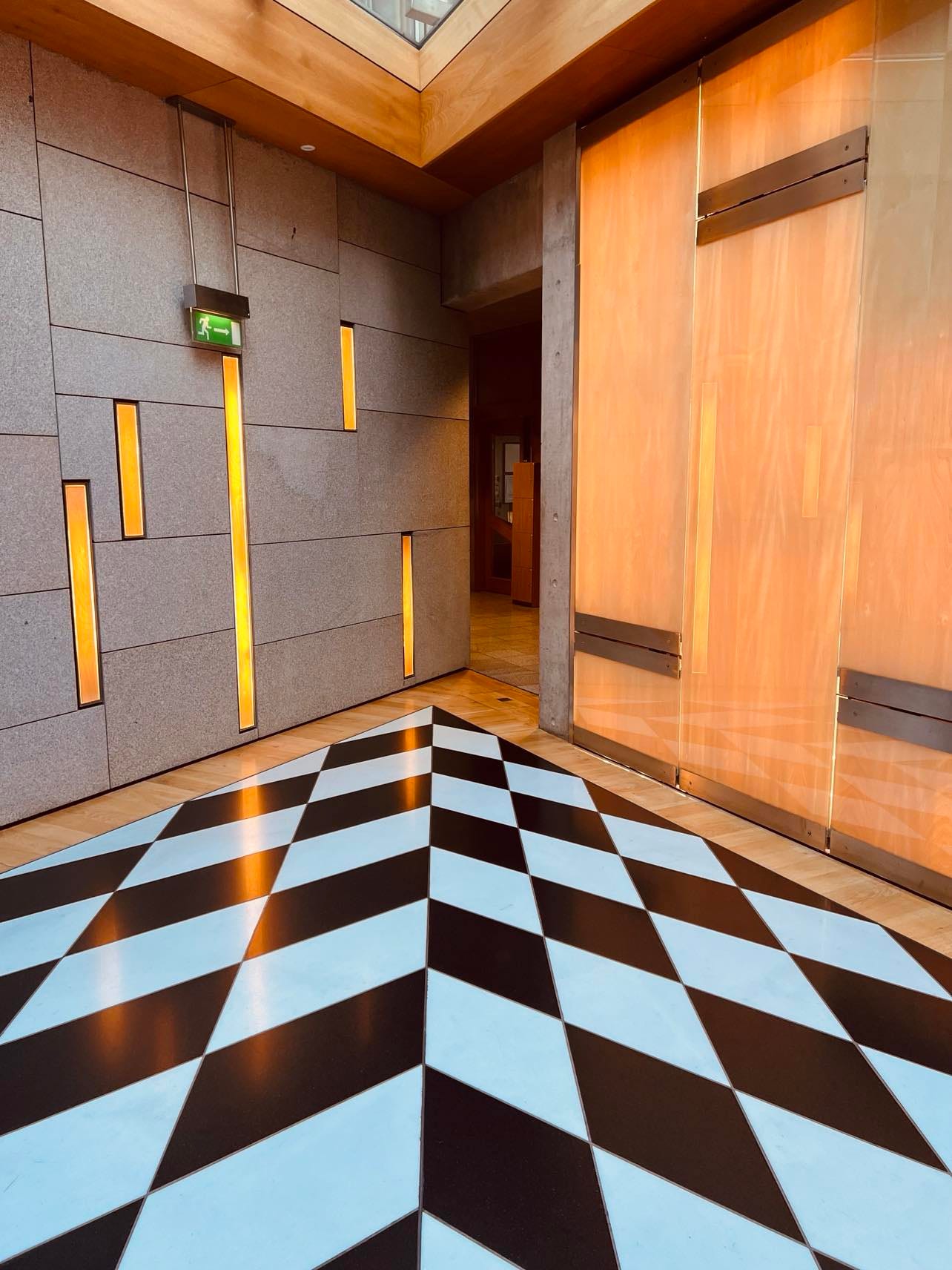

Scottish rock such as gneiss and granite is used on the flooring and walls, along with oak and sycamore in fixtures and fittings. Soaring glass ceilings and windows flood the areas with natural light.

Leaves and twigs

It is said that Miralles, in the first design meeting, produced leaves and twigs to an astonished audience and declared, this is the Scottish Parliament. You can imagine the reaction.

Nowadays, his vision is real. Wherever you look, nature is around you. And each construction, whether it is large and dramatic or smaller and quieter, has an astonishing level of detail.

Interestingly, the Debating Chamber layout was designed to be non-adversarial - other parliaments have opposing parties facing each other. In the Scottish Parliament, they sit side by side, with the party leaders surprisingly close together in rows facing the presiding officer.

Wonderful artwork

Then there’s the artwork. There is so much to commend. Like Shauna McMullan’s Travelling the Distance 2005 – 2006, an installation of 100 porcelain sentences, conceived by the artist as an alternate map of Scotland, and exploring the connection between Scottish women across time and space.

The artist invited women to write a sentence about a woman who had inspired them, from the famous to family members.

Everywhere the message is of inclusivity, of the voices of women, of LGBTQ rights, work in homage to women like Mary Brooksbank (1867 – 1978), the poet, songwriter and activist who started working in Dundee’s jute mills when she was a child.

The words from her Oh Dear Me/The Mill Song, about the long, hard working hours of women in the mills, were included in the Canongate Wall outside the building in 2009.

Sustainability is key

There’s also the sustainability of the building. From its proximity to public transport to the fact that all electricity comes from sustainable sources, and energy from solar panels on the Canongate building is used to heat water in the complex.

A high level of insulation keeps the building warm in winter – the problem is it gets hot in summer.

The solution comes from a computerised system that opens windows when the temperature rises above a certain point, and the windows are open at night to cool down the heavy concrete structure and flooring - the floors are further cooled by water from 25 metre deep boreholes.

As a result, the building achieves the highest rating in the Building Research Establishment's Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM).

The story of the bees

There are so many details, but the bees are a standout for me. On the roof of the building a million bees are housed across 15 hives, cared for by third-generation beekeepers Stuart Hood and his daughter Eilidh.

The bees produce honey, of course, but also their beeswax is used to fill the Great Seal of Scotland, and seal acts of Scottish Parliament.

I don’t want this to become a lecture; this is one of those places you have to see for yourself if you can. Hopefully, like us, you will be amazed at the beauty of it.

It’s open to visitors all year round when Parliament isn’t sitting (usually Mondays, Fridays and Saturdays) and when Parliament is in recess.

Guided tours are free, and can be booked here.

As for us, we headed home again, over the Queensferry Crossing bridge, another marvel of Scottish design admired by the wider world. This one was constructed on time, and on budget.

At times like this, when Scots are feeling beleaguered, when the wealth from our natural resources like oil and gas is plundered, when we’re treated like a colony by client media and Westminster politicians and Scottish identity is denigrated, it’s good to remind ourselves we’re not ‘too wee, too poor, too stupid’.

A visit to the Parliament Building is a tonic and an inspiration for all lovers of design.